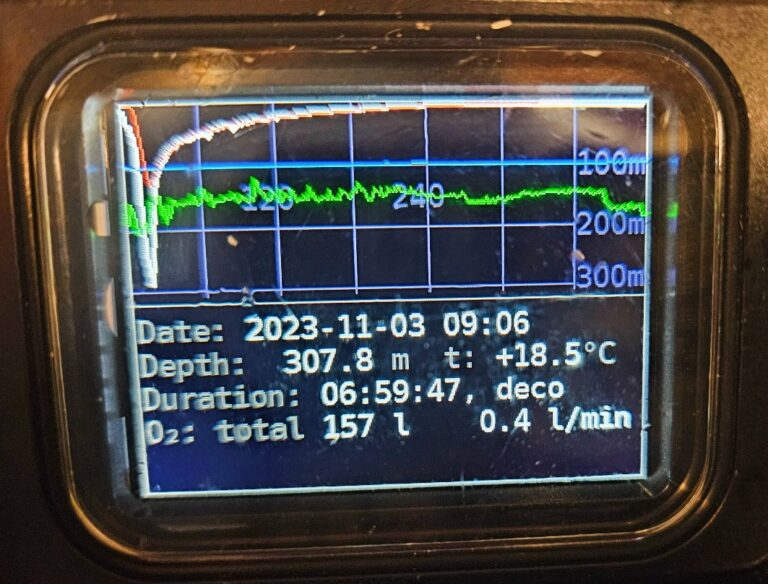

French cave-diver Frédéric Swierczynski has claimed a new world depth record of 308m, following his seven-hour descent into the Font Estramar spring in France’s eastern Pyrenees on 3 November – and having experienced a succession of strange symptoms brought on by too-rapid depth changes.

The previous official record of 283m had been set by South African diver Nuño Gomez in Boesmansgat back in 1996.

Frédéric Swierczynski

Swierczynski, a 50-year-old mechanical engineer from Marseille, is a cave, trimix and rebreather instructor. A diver since he was 12, he made his first solo trimix dive to 120m when he was 18, and started using closed-circuit rebreathers in 2000.

His cave-diving career began in France’s Lot region in 1994 and went on to include notable descents at sites such as France’s Port Miou and Mescla Cave in the Alps, Croatia’s Red Lake, Miljacka in the Balkans and Harasib in Namibia. In May 2019 he claimed a world record for diving at an altitude of 5,870m in Ojos del Salado Lake in Argentina.

The picturesque entrance to Font Estramar

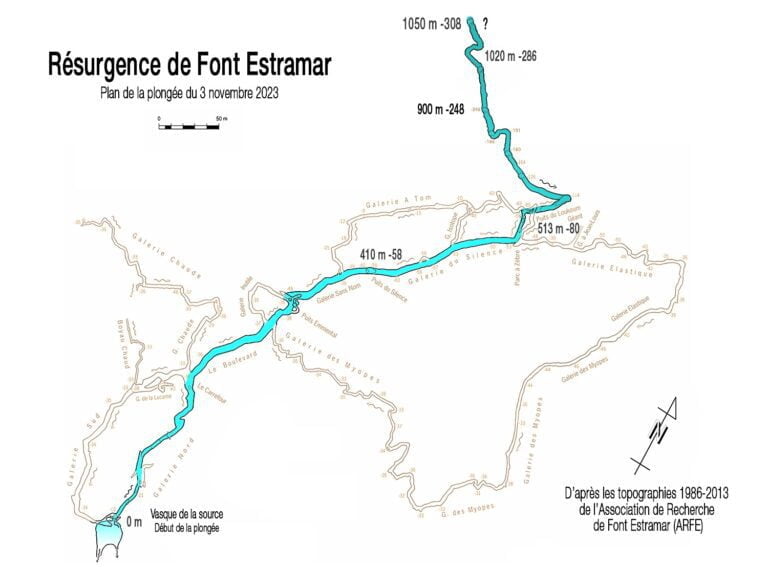

Font Estramar springs from the foot of a small cliff on the edge of a 200m-high limestone plateau, draining into the karst hydrosystem of the south-eastern Corbières. Its brackish water has a constant temperature of 17.8°C.

The system had been explored by divers, including Jacques Cousteau, since 1949. Over the past decade the main breakthroughs have been made by fellow-French diver Xavier Méniscus, who by 2019 had reached a depth of 286m, 1,020m from the entrance.

Jacques Cousteau was among divers to have explored the spring (Piovano)

At least eight divers have died exploring the system, the most recent this July, but Swierczynski, speaking after the dive to Francis Le Guen, who in 1981 had explored the main conduit down to 58m, describes it as “a labyrinthine maze, certainly, and deep, but no more dangerous than many lesser-known, and therefore less-frequented, drowned caves”.

Map of Font Estramar

Equipped for a record

For his November descent Swierczynski wore an Ursuit drysuit over Santi heated underwear powered by the batteries of his two 300m-rated Seacraft Ghost DPVs, which are designed for more than 10 hours of operation.

These would normally be operated in tandem, but Swierczynski was keeping one as a backup fixed behind him to leave one hand free.

Swierczynski in Font Estramar (Laurent Miroult)

Wearing an XDeep harness, he used two sidemounted Czechia rebreathers, breathing on the unit to his left but regularly testing the backup to his right. Their modified CO2 filters would each allow a nine-hour duration.

Swierczynski had abandoned the idea of using regular open-circuit bail-out because the required gas tanks would be too heavy to carry and the regulator would not work properly at depth because of the high flow-rates required.

He was breathing trimix 4/89 (oxygen, helium, nitrogen), which he said he found “more comfortable” than heliox. He also hoped that the narcotic effects of nitrogen would limit SNHP (high pressure nervous syndrome) – though this would still prove to be a problem.

In all he carried six tanks – each CCR included two 2-litre tanks of pure oxygen and diluent, to which Swierczynski added a 2-litre tank of compressed air at 374 bar for suit-inflation and another of 4/89 diluent off-board. The CCRs had 3kg Sofnolime filters, upgraded because of the depth to reduce the risk of CO2 poisoning.

“The descent is so rapid that I directly breathe the 4/89 that I inject,” said Swierczynski. “The recycler then functions like a regulator: the gas does not really have time to circulate in the loop.” He manually controlled the partial pressure of oxygen constantly, choosing to dive with a very low O2 level (less than 1.6) even on decompression stops.

Two Czechia computers with modified Buhlmann algorithms supported each CCR. To reduce decompression times, he adopted a gradient factor of 80/80 rather than his usual 50/80.

Swierczynski also used an ENC 3 navigation console to record his position, coupled with a small propeller to enable displacement to be recorded.

The DPV batteries powered his two main 50,000-lumen Callisto lights, designed and manufactured by Swierczynski himself and mounted on the front of the scooter. He also carried a Phaeton helmet light with a 10hr burntime at 20W to illuminate his hands while laying line, with a Tillytec light with 2hr burntime on his arm. An Isotta camera housing was also mounted on his helmet.

“My goal is to be as light as possible, the most hydrodynamic… to be able to progress under water quickly and without excessive and unnecessary fatigue,” said Swierczynski. To that end he did not use pressure gauges because he claimed to be “so fine-tuned to knowledge acquired during my training and development dives. I know exactly what I am consuming”.

With his “extremely low” metabolism he would consume only 850 litres of trimix 4/89 diluent and 486 litres of pure oxygen on the seven-hour dive.

Prepared to dive

Swierczynski spent months training for the attempt through endurance running in a variety of environments and deep training dives to below 260m.

“Font Estramar resembles a complex labyrinth of corridors and dead ends, where losing your way is not an option,” he said. He acquainted himself with the underwater topography, including navigating a flooded gallery stretching over 1km, refined his decompression curve and practised equipment preparation and adjustment.

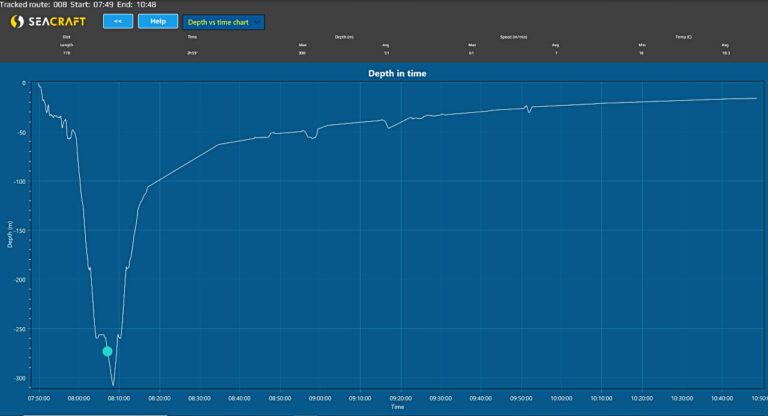

The actual dive started at a depth of 60m, and 10 minutes in he met team-member Patrice Cabanel, who had gone ahead to shoot video. They descended together to 190m, accelerating as they did so – “perhaps too fast” – before Swierczynski signalled Cabanel to stop.

Descent in Font Estramar (Laurent Miroult)

“As I continue my descent, the rock formations become lighter, indicating a shift in geological layers – it’s as if I’m travelling back in time,” observed Swierczynski. He had already visited the horizontal section of the tunnel at a depth of 250-260m many times in training, but it was at this point that he experienced an unusual HPNS symptom.

“I stand up and suddenly experience an unfamiliar discomfort: a dazzling sensation,” he said. “The floor of the submerged horizontal gallery appears flooded once again; it’s like an illuminated sea, shimmering with reflections. I move forward as if in a dream, feeling disoriented.”

Beyond the end of the guideline lay “a black abyss”. He set his DPV at low speed, unwound his line steadily and concentrated on keeping perfect trim to minimise exertion before gliding into an “increasingly expansive chamber” where visibility extended beyond 25m.

He turned when his computer warned him that he had racked up 400 minutes of decompression. “It’s a struggle to break free from the allure of unexplored depths,” he said. “There wasn’t any distress; it was the constraints of decompression time that compelled me to turn back.”

Swierczynski reaches his deepest point

The ascent

Securing his reel at the endpoint Swierczynski set off back up but, as he later realised, was moving “way too fast”. He had been experiencing discomfort in his eyes, which cleared, but after about 16 minutes he noticed that his hands were trembling, another HPNS symptom.

He reached the first deco stage at 130m early, after 28 minutes. At the 90m stop he was joined by deep support diver Bruno Gaidan, who would stay with him for four hours. It was only now that Swierczynski realised how deep he had gone.

Support divers Bruno Gaidan and Patrice Cabanel cross over

Forty minutes in and at the 80m level he suddenly found it extremely difficult to breathe. He checked his CCR, and determined that gas toxicity was not the cause, so he tried the “stomach breathing” he had practised in training, describing the effect as “like sipping through a straw”.

He was also experiencing sharp back pain and a feeling “as if my suit is being crushed, the metal plate of my harness weighing tons”. This sensation lasted for more than an hour, and it was only when he reached the 30m mark that he was able to breathe normally again.

This experience was later attributed to a “massive helium outgassing” resulting from the too-rapid ascent, causing symptoms of apparent spinal cord and kidney injury. He admitted that he had allowed his personal calculations and procedures to over-ride his computers’ warnings, and should have slowed down before the first significant deco stop.

Two hours into the dive, Swierczynski was joined by Franck Gentili on his 50m stop. After 3hr 20min he was approaching the bottom of the exit shaft, with daylight visible, but at the 12m stop he experienced the decompression-related illusion of having lost all bladder control.

The final stopping area at around 6m (Laurent Miroult)

Depth in time chart

Speed in time chart

A home-made deco bell installed at 9m would have allowed him to sit with his legs in the water, though he opted to remain horizontal, observing fish. There was a final 6m stop in the reed beds before he broke the surface, one minute short of seven hours.

“I feel a sense of pride in these moments of pure beauty, in claiming a few dozen metres from the unknown, and in being able to recount this tale,” said Swierczynski, who was already planning his next dive in the terminal well of the Mescla cave in France’s Var region.

The team, from left: Ugo Tonolini, Bruno Gaidan, Yvan Dricot, Michel Ruiz, Frédéric Swierczynski, Franck Gentili, Christian Deit. Christophe Imbernon and Patrice Cabanel are out of shot.

How cave-diver stretched world depth record to 308m (divernet.com)